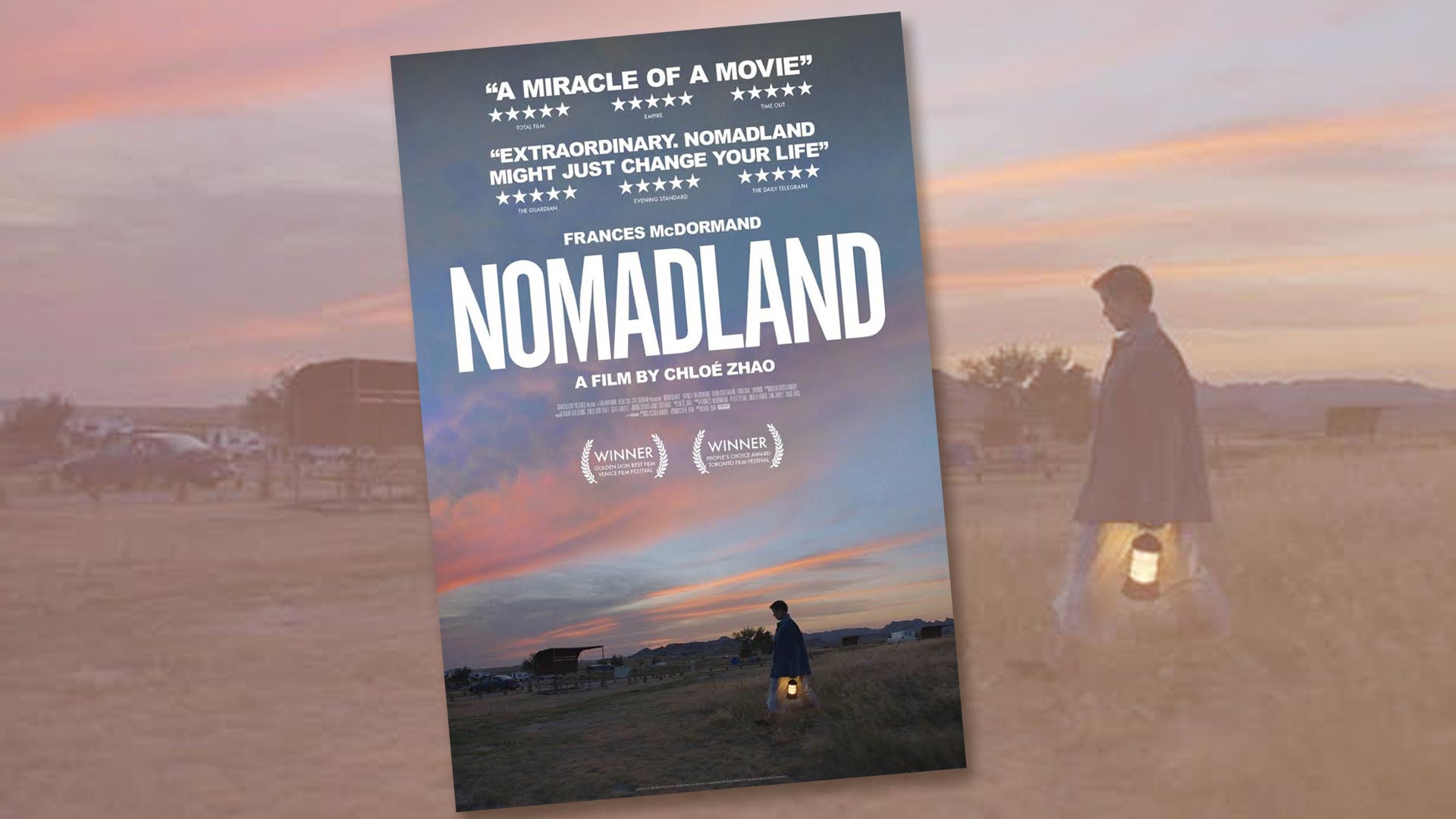

If either actor Frances McDormand or director Chloé Zhao receive an Oscar for Nomadland next Monday, it will be well deserved.

In particular, McDormand’s powerful performance as the widowed Fern shines a light on homelessness and the working poor. But how accurately does it convey the experience of older women who lack housing security?

This hybrid movie/documentary is based upon a non-fiction book by Jessica Bruder, with McDormand playing the lead ‘character’, alongside a real life supporting cast.

It blurs genres to offer a candid and unpredictable view of the precarious existence of the nomadic working poor in today’s America.

Yet it resists the urge to present Fern as a victim. Far from it. As she states, firmly, she may be houseless, but not homeless.

She’s also portrayed, at times, as a woman with great agency – free as a bird, striding wild coastal shores, choosing to leave a potential romance and secure home for an uncertain future on the open road.

Despite her protestations, however, technically, she is homeless. When her van needs repairs that she can’t afford, she seeks both refuge and the required $4000 from her home-owner sister. Lucky for her that her sister has the money and, after an awkward home truth or two, is prepared to fund Fern’s return to life on the road.

Nomadland is an important movie which manages to highlight many socio-economic issues without offering easy answers or moral judgements.

Which makes its insights well worth exploring from an Australian perspective, particularly the spike in homelessness amongst women aged 60 and above.

A few facts about older women and homelessness in Australia:

- There has been a 30% increase between 2011 and 2016 in women aged 55+ who are defined as homeless

- There are 63% more older women accessing homeless services than there were five years ago

- At retirement age, one third of women are suffering from income poverty

- 35% of women have no super at all

- Those who do have super, have approximately half the average account balances held by men of the same age.

The risk factors for homelessness include being a renter, not employed full time, being a lone parent and having been at risk before. The combination of being a low income woman, who is ageing, with low retirement savings in a booming housing market is a perfect storm. When any of these factors are exacerbated by the loss of a job or long term relationship, or poor health, the slide into homeless status is all too often the next stage.

I am not a Fern. I am extremely grateful to have the luxury of a roof over my head and (fingers crossed) long term prospects of keeping it. I salute those who embrace a life on the road, going wherever that road leads, for as long as they can. But I am not confident that there won’t come a day when they can no longer live on the road. And without savings or property, will be at the mercy of a meagre government pension or limited charity support with which to eke out their remaining days.

Ultimately I don’t believe the life shown in Nomadland is a question of ‘freedom’ – whatever that means.

Freedom can be short-term and illusory. What is really at stake here is the question of dignity. A consideration of the causes and results of homelessness suggests that the major missing element in the lives of the young, old and those in-between who lack secure accommodation, is invariably that of dignity. Which means getting reliable work, enjoying secure relationships, maintaining self-esteem, and positive mental and physical health are all reasonable life expectations which are significantly reduced for the Ferns of this world, be they on a friend’s couch, in the car, or on a park bench tonight.

Above all, having secure housing is a basic human right. Australia is a signatory to

to the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) that states:

‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family, including …. housing’.

But we are not observing, let alone delivering on the obligation required by our status as a signatory. The time to avert homelessness is at the stage of early intervention, when jobs and homes become precarious, not by building social housing 20 years later than needed, as a last resort.

So go and see Nomadland and judge for yourself. Is this the life? Or is it a precursor to a much less dignified, tougher, old age?

Kaye Fallick is a writer and member of the Steering Committee of EveryAgeCounts campaign which fights ageism.

[ends]

Don’t just read this, do something.

Learn more – read the report by Dr Kay Patterson, Age Discrimination Commissioner, AHRC, Older Women’s Risk of Homelessness

Give to charities such as the Older Women’s Network, NSW

Join EveryAgeCounts, the campaign fighting ageism for all generations.

And next time you walk past this person on the street, at the very least, spare them a smile, word, note, or all three. Who knows, one day it could be you.